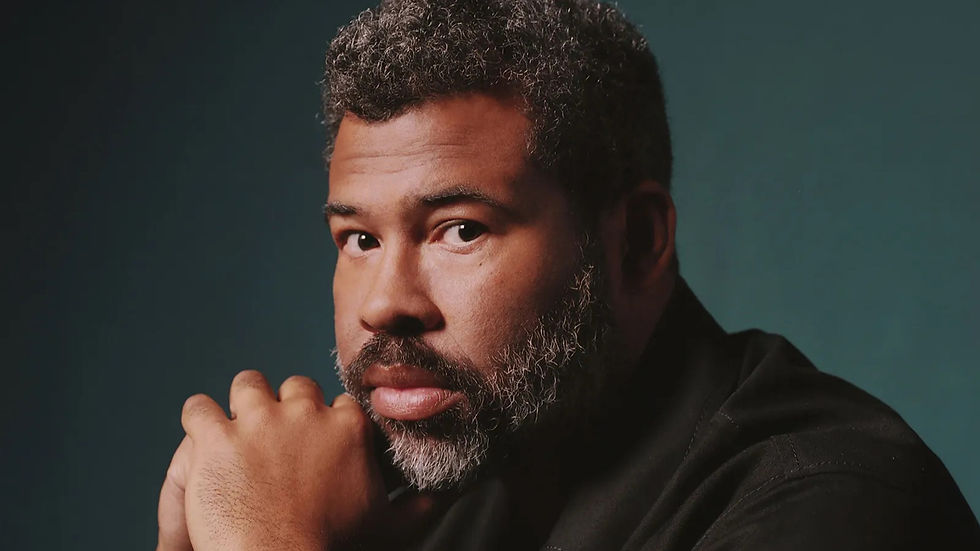

I GET SO EMOTIONAL WATCHING JORDAN PEELE FILMS

- Brittanee Black

- Dec 17, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Feb 27

So, there's this one a scene from 2019's Us that literally haunts my dreams. When asked who she and her fellow-invaders are, the Tethered version of Addie (or, I guess, the swapped original version), her voice gulping and hoarse as though she were drawing in her final breath, replies, “We’re Americans”, making a seemingly simple, two-word retort, in context, the film's most sinister line. It marked a point where it became clear to me that Jordan Peele, with great deliberation, was stepping beyond the confines of traditional horror to travel further, deeper, with a more experimental sensibility and a more resolute indictment of America's "post-racial" blindspots.

Black is in Fashion.

Whew. Ok.

Jordan Peele has only directed three feature films, but in that time he's already emerged—like black Ariel from under the sea—as a master of horror-thrillers with a social edge and biting takes on race and class. But what's more interesting is Peele consistently creates works that move him, that excite him, that intrigue him, no matter what expectations society might have, opting for atmospheres that are both frightening and all too familiar to Black people, and doesn’t concern itself with being relatable to white audiences. At once terrifying and iconic (and beautiful), Peele illustrates a helplessness Black people can often feel when they're, say, the only Black face in a room. Or in the face of biased legislation. Or in the prison industrial complex. Or in the many other oppressive spaces that exist in a world designed to other Us.

During my freshman of college, on my very first day, I was grouped with other students—all white—during an orientation exercise. After fielding one uncomfortable question after another (and some unprompted factoids about George Washington Carver and peanut butter 🙄), one of said group-mates took the opportunity to ask if I'd "gotten in" because of affirmative action, followed up with "must be nice to have that advantage," oddly spoken without malice but with kudos, the tone of a parent telling a child "way to go, kid."

That moment, and many subsequent moments, were an almost exact mirror of a scene in 2017's Get Out, when protagonist Chris Washington attends the Armitages' annual get-together and soon finds himself surrounded by dozens of wealthy white people wasting little time bringing up his race in ways they seem to think are progressive and respectful. One particular guest starts talking to Chris about how he imagines it's beneficial to be a Black man in the current era and how it's even fashionable. For white audiences, it's one of the film's cringiest moments. For me, it's validation. It's confirmation that every time I'd been gaslit into thinking I was "being too sensitive", "couldn't take a joke", or "reading too much into" a situation, I wasn't. I was right to feel to uncomfortable. And I was right to protect my boundaries.

Once Upon a Time There Was a Girl.

One key theme of Peele's films I immediately latched onto is the idea of "other"-ism. It wasn't long into 2022's Nope that I noticed in all three Peele-directed films, the central fear is of being replaced by an "other". In Get Out, it’s the Armitages, the Order of the Coagula and their special lobotomy that makes Black people passengers to their own existence. In Us, it’s a cult—the Tethered—no less committed to taking over the lives of their victims.

Their humanity sidelined, the Tethered are a personification all things unseen, unheard, and unacknowledged (you know, like micro-aggressions). And themes of replacement pop up again, albeit from a slightly flipped perspective, in Nope, a spin on the terrifying, mere idea of the unwelcome arrival of outsiders—black people being among them—echoing a sentiment a subset of Americans strongly believe; making space at the table for "other" people will lead to their own space being taken away (musical chairs styles). What makes Nope so prescient is that it amplifies those invisible lines of power drawn between the "us" and the "them" to the point where there's even a character who believes one of "us" must be sacrificed in order to make room for or appease the "them". It's even funny to think this message is likely more relevant now than it was at the time the script for Nope was written, as many of the criticisms lobbed against current representation, visibility, and inclusivity movements often boil down to "if we make room for you, what are you taking away from us?"

They Say Everyone's Got Demons, Right?

I think I'd be remiss if I didn't briefly touch on 2022's Wendell and Wild, not directed, but co-written and produced by Peele, and a film that touches on two other themes that pop up again and again in Peele's works—trauma and demons. Of the film Peele said, "This story is about conquering your personal demon as much as learning how to wear your fears.

Allowing them to shape your power." Kat Elliott, the film's protagonist, is a 13-year-old, green-haired, punk, badass, sure, but at her root, she's a survivor. And despite being a fully grown woman, it was through her that I found the will to begin the journey of unravelling my own demons, and the search for my own power.

What If I Told You Today You'll Leave Here Different?"

From the start—from way back in his Key & Peele days—Jordan Peele announced loud and clear that there's power in storytelling and that he was both willing and able to use that power to make a statement about the corners of the black experience that are too often cloaked in shadow. Parts that I myself often cloak when speaking to a non-black audience. And I don't think I'm alone in that hesitancy to speak candidly, even when among friends.

When we talk about the need for representation, the need to be "seen on screen" or to "see oneself in fiction", it's too often translated literally. Put a black face on the screen, doesn't matter where, and you've done your job. But it's rare that this media pandering actually results in feeling seen. But with what Peele has done—tackling themes of replacement, displacement, trauma, identity, and autonomy, not just addressing it but rectifying an imbalance in the types of stories allowed to be told—its in the throws of his storytelling that I do feel seen. And heard, and hugged, and consoled, and shook. But, ultimately, brave.

Comments